Brief History of Chervonohrad

Foundation of Chervonohrad (Krystynopol)

From the end of the 10th century, these lands were part of Kievan Rus, and from 1234 - part of the Galicia-Volyn Principality with its capital in Belz. In the 14th century, there was a continuous struggle for the Belz lands between Lithuania, Hungary and Poland, which alternately seized the region, until in 1387 the Polish queen Jadwiga established the Polish power in this territory. In the 15th century, Belz became a voivodeship (province) of the Kingdom of Poland, and for the next few centuries the history of the Galician lands was connected with the history of Poland.

The town of Krystynopol was founded by the Polish noble, magnate and military leader Feliks Kazimierz Potocki (1630-1702). The official year of foundation is 1692. He named it after his wife Krystyna. His grandson Franciszek Salezy Potocki (1700-1772) built a palace in Krystynopol and founded the monastery of the Basilian Order (1763). In the 1760s, Giacomo Casanova visited the Potocki Palace in Krystynopol.

The town began to grow around the palace. In 1772, after the first partition of the Commonwealth, Krystynopol, along with all of Galicia, came under the control of the Habsburg monarchy. The Pototski soon left the town.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were a period of decline. Only in the second half of the 19th century, Krystynopol began to develop again - a mill was rebuilt, a brewery and a distillery were opened, and the grain trade revived. In 1884, a railroad was laid through the town. As of 1890, 3,565 people lived in Krystynopol, including 2,722 Jews, 556 Poles and 287 Rusyns.

More historical facts…

Chervonohrad (Krystynopol) in the first half of the 20th century

In August 1914, during the First World War, the troops of the Russian Empire entered the town. In the summer of 1915, Austrian-German troops retook Galicia.

On November 1, 1918, during the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic was proclaimed. This historical day for Ukrainians was the beginning of the Ukrainian-Polish war. Poland declared its independence on the same days and also claimed the territory of Galicia. The fighting also affected Krystynopol.

In July 1919, the Ukrainian Galician Army was forced to withdraw to the territory of the Ukrainian People’s Republic and Galicia returned to Polish rule. Krystynopol became part of the Lviv Voivodeship of Poland. During these events, the population of Krystynopol decreased by about one third.

In September 1939, during the Second World War, the town was occupied by German troops and Krystynopol was included in the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region. Most of the Krystynopol Jews were expelled by the Germans to the territory controlled by the USSR. In September 1942, the remaining Jews were deported to the death camp in Belzec. On July 18, 1944, Krystynopol was liberated by Soviet troops and returned to Poland.

Chervonohrad in the second half of the 20th century and beyond

On February 15, 1951, according to the agreement on the exchange of territories between the USSR and Poland, Krystynopol was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR. The reason for the exchange of territories was the presence of coal deposits near Krystynopol, which were exchanged for oil and natural gas bearing territories. Krystynopol received a new name - Chervonohrad (Krasnograd in Russian, which literally means “Red City”). The exchange of territories was accompanied by the resettlement of a significant part of the local population.

The basis on which Chervonohrad began to develop was coal mining. Workers and employees from different regions of the USSR, miners from the Donbass and the Moscow region coal basin were involved in the construction of coal mines and new city blocks. For the construction of enterprises and housing, a brick factory, plants for reinforced concrete products and large-panel blocks, metal structures, and a woodworking plant were built.

In Chervonohrad, new wide streets were laid with a lot of public gardens and green spaces. The first mine was commissioned on December 25, 1957. In 1959, about 12 thousand people lived in the town.

In 1977, the population of Chervonohrad was about 53 thousand people, having increased more than four times in less than twenty years. The basis of the economy was coal mining, there were also a factory of reinforced concrete products, a dairy plant, a woodworking plant, a garment factory, a hosiery factory, a branch of the Lviv Polytechnic Institute and a mining college. In 1979, the Chervonohrad coal preparation plant was put into operation with a capacity of 9,600 thousand tons per year (the largest in Europe at that time).

In 1989, about 72 thousand people lived in this city. On August 1, 1990, in Chervonohrad, for the first time in the Ukrainian SSR, the monument to Lenin was dismantled by decision of local authorities and with a large gathering of local residents - a month and a half earlier than in Lviv.

In the 1990s, due to the disruption of economic ties caused by the collapse of the USSR and the transition to a market economy, most large enterprises went bankrupt and closed in Chervonohrad, the output of the remaining ones decreased significantly. The population of the city began to decline.

On June 24, 2021, Chervonohrad received its branding - logo and slogan. The slogan of Chervonohrad is the phrase “The city of the strong!”.

Pictures of Chervonohrad

The Hymn of Labor monument - one of the symbols of Chervonohrad

Author: Alekseij Titus

Monument to Taras Shevchenko in Chervonohrad

Author: Viktor Gorbatch

Chervonohrad Railway Station

Author: Savostikov Alexey

Chervonohrad - Features

Chervonohrad is divided by the floodplain of the Western Bug River into the old city (in the past - Krystynopol) and the new city (built in connection with the development of the coal basin), which are connected by a dam. The distance to Lviv is about 70 km.

It has a favorable geographical location and a well-developed transport network (Lviv-Kovel-Brest (Belarus) highway, Belz-Chervonohrad and Radekhiv-Chervonograd highways, Lviv-Kovel and Chervonohrad-Rava-Rus’ka railways), borders on Poland.

The climate in Chervonohrad is temperate continental with features of the Atlantic-continental type, characterized by mildness and high humidity. The average temperature in January is minus 4 degrees Celsius, in July - plus 19 degrees Celsius.

Since 1951, Chervonohrad has become one of the centers of the newly formed Lviv-Volyn coal basin. Despite the sharp decline in coal production during the years of Ukraine’s independence, several coal mines continue to operate in the city. Today, its economy is based on wholesale trade, retail trade, and coal mining.

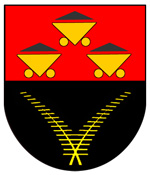

The coat of arms of Chervonohrad is divided into red and black fields. In the red field there are three golden trolleys with black coal, in the black field - two golden fern branches. The red color symbolizes the name of the city (Chervonohrad literally means “Red City”), while the black color and coal trolleys emphasize the role of the coal industry in its development. Fern branches symbolize wealth and prosperity.

Main Attractions of Chervonohrad

Potocki Palace (1756-1760) - an architectural monument of local importance. The palace was built by the owner of the town, Franciszek Salezy Potocki, and became his residence. The project belonged to the French architect Pierre Rico de Tirrezhelli, who later became the architect of the Prussian King Frederick the Great. Wilanow Palace in Warsaw was taken as a model.

At one time, this palace was considered a real pearl of architecture, combining two styles: baroque and early classicism. Around the palace a large park in the French-Italian style was laid. Unfortunately, not much has survived from the palace complex. This is due to the frequent change of owners, numerous fires and rebuilding.

Today, the Potocki Palace is the only monument of palace architecture of the mid-18th century in the north of Lviv Oblast. It houses a branch of the Lviv Museum of the History of Religion, where you can see works of Ukrainian sacred art of the 17th-19th centuries and icons of the 15th-16th centuries.

The museum also has a permanent exhibition “History of Krystynopol in the 17th-19th centuries”. The exhibition hall (former ballroom), given the excellent acoustics, is also used for concerts, both by famous artists and local musical groups.

Catholic Church of the Descent of the Holy Spirit (Orthodox Church of St. Vladimir) (1701-1704) - a majestic baroque building, which is the most prominent church in Chervonohrad and the oldest one in the city. In the 1950s, the church was closed. The building was used for other purposes and was falling into disrepair.

In 1988, when the 1000th anniversary of the baptism of Rus’ was celebrated, the church was handed over to the local Orthodox community and became the Church of St. Vladimir. After the restoration, the appearance of the building changed. Four smaller domes painted blue and decorated with stars were added near the main dome. Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, 20.

Basilian Monastery and Church of St. Yury (1771-1776) - architectural monuments of national importance belonging to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. The monastery was founded by the Polish nobleman Franciszek Salezy Potocki for the Basilian Order in 1763. The construction was led by the Czech architect Johan Kasper Selner.

The architecture of the monastery cells and the Church of St. Yury combines features of the late baroque and classicism. In 1980, a branch of the Lviv Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism was opened here, and the former cells of the monastery were used as an art gallery. In 1989, the museum was moved to the former Potocki Palace, and the church buildings and cells were given to the local Greek Catholic community. Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, 21.

Art Museum “Sokalshchyna”. This museum was opened in 1981, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Chervonohrad joining Ukraine. In total, there are about 1,000 exhibits: works of folk art, household items, and antique furniture. This part of Ukraine is famous for its masters of embroidery: black embroidery is a rarity of the museum, each shirt is an exclusive product, and not a single ornament is repeated.

Also here you can see an exhibition of unique examples of black ceramics, pysanky (painted Easter eggs) made by Taras Horodetsky, and the interior of a house of the late 19th - early 20th centuries. Bohdan Khmelnytsky Street, 16.